Entertainment Contracts – From book to screen

Film rights are the rights under copyright law to make a derivative work, in this case a film, derived from an item of intellectual property [1], in the case of this article a book.

There are basically two reasons why, from the earliest days of film industry, books have been used as the basis for the narrative structure of greats films.[2]

The first is that a novel is one view for testing the market, for verifying in advance the successful of a story. The second reason is aesthetic: movies and books share many common features such as plot structure, characters and tone.

“It has been estimated that in one year approximately one third of all films produced in Hollywood are based on previously published literary work; 42% of the Oscars awarded for best picture are based on novel, as opposed to 28% based on original screenplays[3].” Yet there are some difficulties in using a book for making a film. “In film criticism, it has always been easy to recognize how a poor film “destroy” a superior novel.”[4]

Entertainment Contracts -Films became different artistic entity from the novel on which they are based.

Adaptations can be tricky and do not always result in artistic and/ or commercial success. There are thousands of examples of writers who are upset about how the film transformed their material.

A case that might illustrative of an author’s regrets is that of “The Natural”[5]. I once heard (and this may be apocryphal) that Barry Levinson changed the story’s ending to be uplifting rather than depressing what the novelist Bernard Malamud so much regretted that it hastened his death [6].

Entertainment Contracts – writers who gave up the rights to their work

There are also plenty of stories about writers who gave up the rights to their work and, despite being paid a lot of money, loudly regretted it.

One example is the author Anne Rice when she sold the rights to “Interview With The Vampire.“ When the lead was cast, she told the Los Angeles Times, “I was particularly stunned by the casting of Tom Cruise, who is no more my Vampire Lestat than Edward G. Robinson is Rhett Butler. [7]”

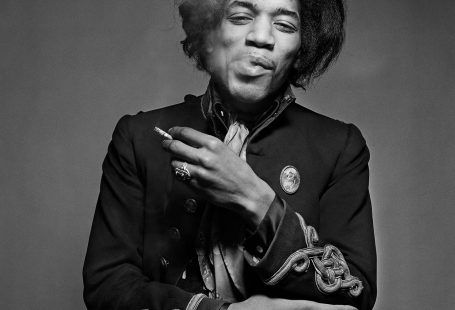

At the other extreme, there’s the standard tale of the writer who sold the rights to his work for a negligible sum, while the film went on to make millions. One example is the writer Chuck Palahniuk with his first novel “Fight Club.”

Although Palahniuk did go on to garner fame and a tremendous boost in book sales because of the film.[8]

While some writers are relaxed about signing off on their work, like author Jonathan Lethem with his Promiscuous Stories Project – with which, a couple of years ago, he “…decided to start giving away some of his stories to filmmakers or dramatists to adapt [9]” – others are militant about maintaining control over their characters and storylines.

Author J.K. Rowling is an example[10]: “she could impose demands on the studio, including having a say in the choice of director, and even demanding that the screenplay of the first book remain exactly as written in the novel. This is because Harry Potter was then, and still is, a monster hit.[11]”

Entertainment Contracts – Another iconic case is that of “Mary Poppins.”

The relationship between the book author Pamela L. Travers and Walt Disney can be qualified as an epic personality struggle over rights. Mrs. Travers would never agree to Poppins/Disney adaptation, though Disney made several attempts to persuade her to change her mind.

Disney already had invested a lot of money in the film before he had obtained the rights while Mrs. Travers “…disapproved of the dilution of the harsher aspects of Mary Poppins’s character, felt ambivalent about the music and disliked the use of animation to such an extent that she ruled out any further adaptations of the later Mary Poppins novels.”[12]

So fervent was Travers’ dislike of the Walt Disney adaptation and due to the way she had been treated during the production, that well into her 90s, when she was approached by producer Cameron Mackintosh to do the stage musical, she only acquiesced upon the condition that only English born writers (and specifically no Americans) and no one from the film production were to be directly involved with the creative process of the stage musical. This specifically excluded the Sherman Brothers from writing additional songs for the production even though they were still very prolific.[13]

Entertainment Contracts – Authors sometimes are concerned about credits.

There have been a number of cases where authors were so distressed by treatment of their work that they required that their name be removed from the credits.

Michael Crichton[14], better know as the author of “Jurassic Park” and “The Lost World”, in addition to his screenplay credit in “Jurassic Park,” is credited in “Jurassic Park” and “The Lost World” with “based on the novel by”; and in “Jurassic Park III” his credit is “based on characters created by.”

These are some examples and reasons why authors should try to find some ways of control their own rights and exploit their creations maintaining same control on them. The agreement to choice for these purposes is the option agreement.

[1] See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Film_rights. [2] “Films like “The Big Parade” by King Vidor in 1925 was based on a story by author Laurence Stallings; or Mary Shelley’s Gothic novel “Frankenstein” was made for the screen by James Whale in 1931. James Hilton’s best selling novel “Lost Horizon” was adapted for the screen by screenwriter Robert Riskin and made into a film in 1937 by Frank Capra. Two greats of American cinema were made in 1939 and were adapted from books: the “Wizard of Oz” and “Gone with the wind.’” See From books to screen, Mining literary works in the movie business, by Daniel M. Satorius, in 24 Ent. & Sports Law. 1 (2006-2007). [3] See Selling Rights, Fourth Edition, p. 215. [4] It has been known for film companies to acquire rights in a book in order to use only the title, or to use the personality of one character from the story in the context of a very different plot, destroying completely the harmony or the integrity of a work. See also Novels into Film, by George Bluestone, p. 62. [5] The Natural is a 1952 novel about baseball written by Bernard Malamud. A film adaptation of The Natural starring Robert Redford as Roy Hobbs was released in 1984. [6] Thom Powers, documentary producer and filmmaker. [7] See http://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/7577.Anne_Rice [8] See http://newenglandfilm.com/magazine/archives/2009/01/adaptationrights, Buying and Selling the Rights to Adapt a Film, By Kate Fitzgerald [9] See http://www.jonathanlethem.com/promiscuous.html [10] HARRY POTTER (Rowling’s royalties are close to £400million): The character was created by JK Rowling in a cafe in Scotland and went on to appear in six bestselling children’s books – topping the charts in almost every country where sales are registered. See Initial Print Runs for Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, available at http://www.veritaserum.com/books/book6/ [11] See Never sell…always license, by Lee Penhaligan. [12] Mary Poppins and her mystic Aussie creator Catherine Barnes, 5 September 2004, The Express on Sunday. [13] This also comes up in a new documentary called THE BOYS: The Sherman Brother’s Story. [14] John Michael Crichton (October 23, 1942 – November 4, 2008) was an American author, producer, director, screenwriter, and medical school graduate, best known for his work in the science fiction, medical fiction, and thriller genres.

Entertainment Contracts: If you need more info about, do not hesitate to contact us.

Dandi Law Firm provides legal assistance in Copyright, Film and New Media. Check out our Services or contact Us!